Finding a Research Lab: Undergraduate Mackenzie Noon Bridges Biology and Computer Science

Quick Summary

- Mackenzie Noon is an undergraduate researcher studying cancer at the chromosomal level

- During healthy cell division, chromosomes must separate neatly through a multi-step process that results in two daughter cells

- Noon’s research concerns disruptions to this cellular process that result in cellular structures commonly found in cancer cells

Mackenzie Noon’s upbringing in Redlands, Calif. was a synthesis of biology and computer science. Noon’s mother—a physician—taught her son the basics of biology, while his father introduced him to the joys of DIY and computer programming. Together, they built bottle rockets and Tesla coils, and Noon programmed his own video games.

By the age of 15, Noon had turned his curiosity into more than just a hobby. He split his time between high school at The Grove School in Redlands and an internship with a company called Cybertek. While initially hauling ladders, he eventually began installing routers and configuring networks for the company and its customers.

“I worked for a networking company setting up computer networks as a summer job, but I was also interested in biology,” recalled Noon. “But my experience with biology was probably a lot less hands-on because of the nature of the thing. Everybody has a computer in their house, but a genetics lab? Not so much.”

Getting involved in science

When he enrolled at UC Davis, Noon gravitated towards genetics. Advances in bioinformatics enticed him, and he was taken with news stories he’d read about mosquitos genetically engineered to fight malaria.

“I thought, “Oh my god, I’ve got to get into this. This is so cool,’” said Noon.

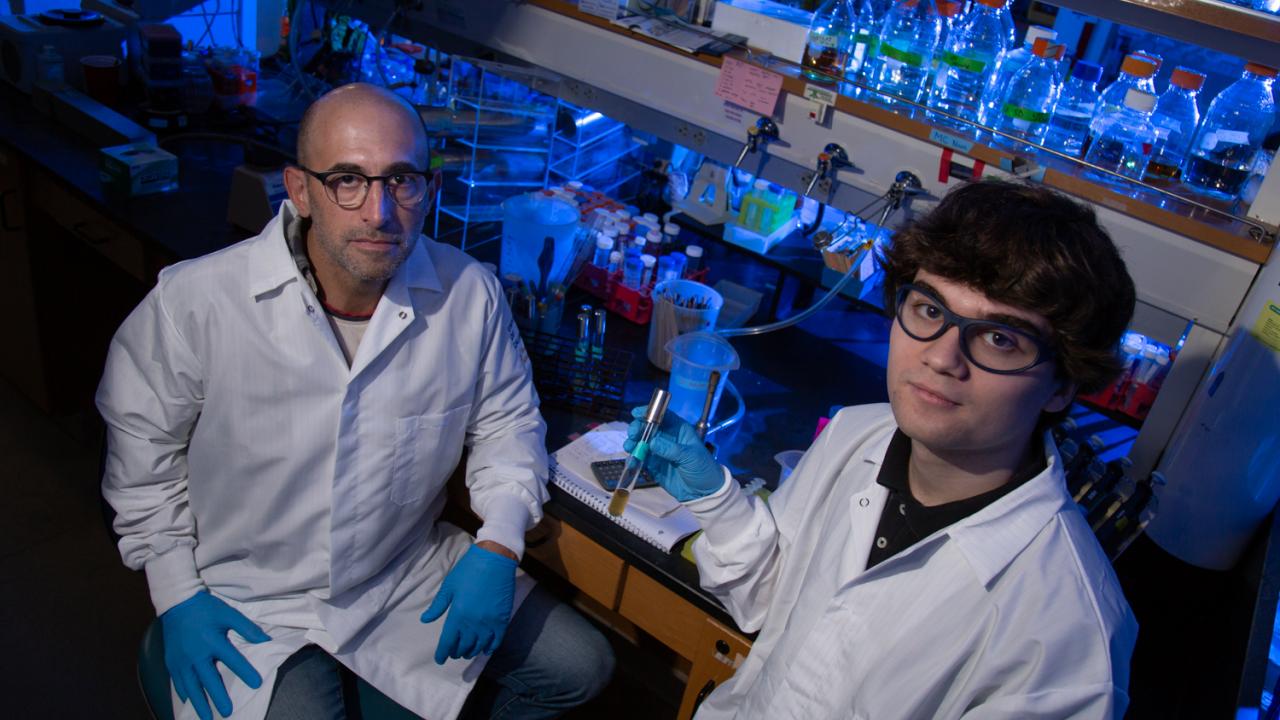

Now, Noon is an undergraduate researcher in the lab of Professor Ken Kaplan, Department of Molecular and Cellular Biology, where he studies cancer at the chromosomal level. Cancerous cells commonly have abnormal numbers of chromosomes and other aberrations. Noon said he finds the foundational nature of the research rewarding.

“Studying the process of chromosome segregation might potentially lend some insight into novel therapies for cancers,” he said.

The path to undergraduate research

Noon was eager to get involved in research after arriving at UC Davis. He enrolled in a couple of Course-based Undergraduate Research Experiences (CUREs) courses, including one called “The Nectar Microbiome,” and learned basic laboratory techniques, like polymerase chain reaction and gel electrophoresis. He found the courses rewarding but was eager to dive into his very own independent research.

“I went to the Undergraduate Research Center because I heard that’s where you’re supposed to go and I said, ‘Okay, how do I find a lab?’”

Noon identified numerous labs of interest but narrowed his search after attending Kaplan’s “Road to Research” seminar hosted by the Biology Academic Success Center. Afterwards, they exchanged a few emails, and Kaplan invited Noon to attend one of his lab’s weekly meetings.

“I am typically cautious about taking first year students into my lab, as they are often overwhelmed by the quarter system and generally benefit from the maturity experience brings them,” said Kaplan. “Mackenzie convinced me otherwise. At our first meeting he showed a remarkable level of maturity, an impressive intellectual engagement in our conversation and a degree of thoughtfulness that made me eager to chat with him more.”

Soon, Noon was completing safety training and learning Kaplan Lab basics, like how to culture and dilute budding yeast (Saccharoymyces cerevisiae), which the Kaplan Lab uses as a model organism for studying chromosome segregation.

Studying yeast to stop cancer

During healthy cell division, chromosomes, which carry vital genetic information, must separate neatly through a multi-step process that results in two daughter cells. Integral to healthy separation is a region of the chromosome called the centromere, which recruits proteins responsible for dividing the cell in two.

Noon’s research projects concern disruptions to this cellular process that result in structures called chromatin bridges. These linkages keep sister chromatids—identical ends of chromosomes—stuck together and are commonly found in cancer cells.

“Mackenzie is helping us understand how autophagy—a process by which cells undergo ‘self -eating,’—pathways in cells are connected to adaptation to drugs like hydroxyurea that inhibit DNA replication,” said Kaplan. “There is long history of using this strategy to defeat cancer cells; the logic is that since they divide more than ‘normal’ cells they will be sensitive to drugs that make replicating their genome difficult.”

But according to Kaplan, cancer cells can quickly adapt to treatments meant to stifle their replication.

“Mackenzie’s work suggests that an important part of this particular adaptation pathway is the cell’s ability to selectively ‘degrade’ specific parts of the cell,” said Kaplan. “One possibility is that inhibiting both pathways—DNA replication and autophagy—will create a big enough impediment to cancer cell proliferation to prevent chemotherapeutic resistance. Mackenzie’s early results are tantalizing and now he’s off to the races to figure out the molecular mechanisms that explain his observations.”

Sifting through biological data

While only a sophomore, Noon currently hopes to pursue a research career after completing his undergraduate degree. Until then, he’ll continue to make the most of the plentiful research resources on campus.

“UC Davis has some really remarkable resources and I think that often times people are not made aware of them,” Noon said. “The Undergraduate Research Center is a great way to get hooked up with a real academic laboratory.”

Noon’s also got his sight set on the future of biology. With technologies rapidly advancing, computer science and big data are continuously becoming more important to the life sciences realm, especially in genetics, an area known to generate large swaths of biological data.

“Biology is very complicated,” Noon said. “Figuring out where to investigate is kind of a big data task.”