How Does a Fish Get Its Shape? Students Explore Smithsonian National Fish Collection to Find Answers

Quick Summary

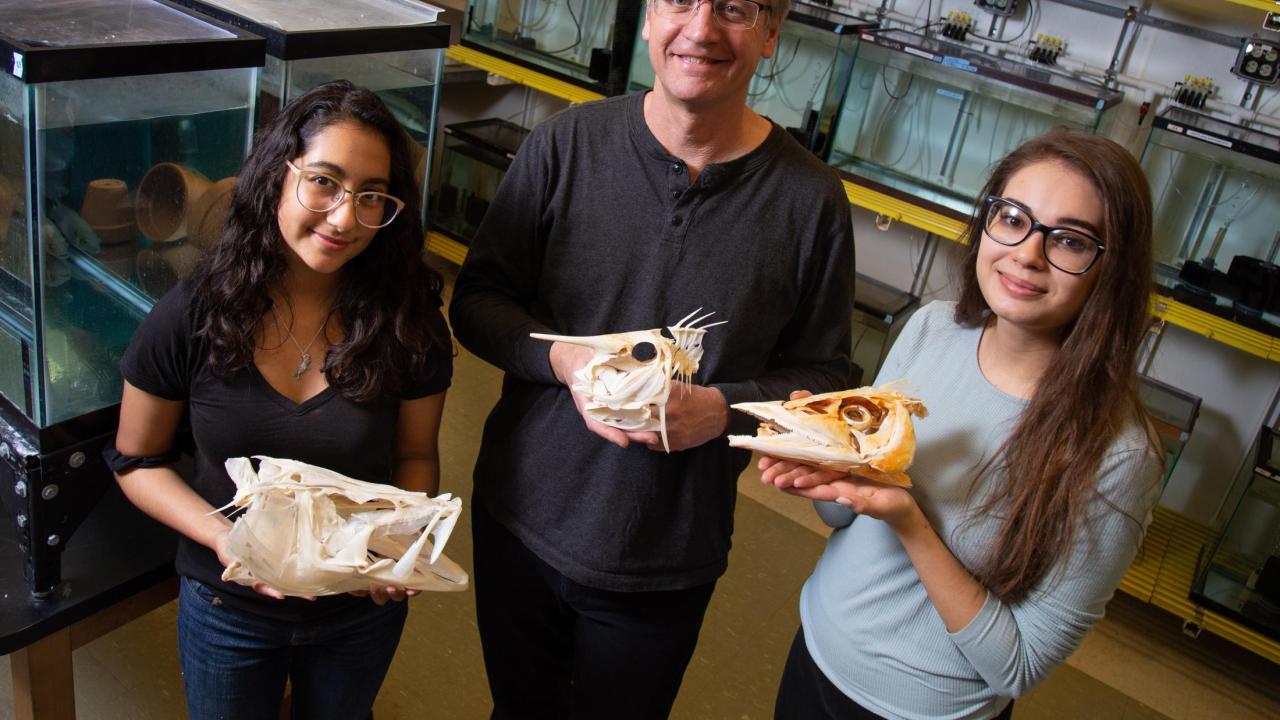

- For the past three summers, Professor Peter Wainwright enlisted undergraduates to help him amass data on fish body shapes

- They've collected data from 16,000 specimens from the National Fish Collection down in Washington D.C.

- The team hopes to use the dataset to answer fundamental question about fish body shapes

There are 32,000 species of fish swimming in the Earth’s waters and the diversity of their shapes is astounding. Consider the eel—long like a snake with needle teeth; or the Bluefin tuna—a streamlined, oval-shaped behemoth; or the seahorse—with its S-shaped body, protruding snout and spiraling tail.

What evolutionary factors shaped these fish’s bodies? And how, why and when did this diversity explosion occur?

Professor Peter Wainwright and his colleagues are probing these questions, but doing so requires a unique view, one that doesn’t necessarily come from fieldwork.

“The thing I’m most fascinated by is the diversity of life,” said Wainwright, who holds appointments in the Department of Evolution and Ecology, the Center for Population Biology and the Coastal and Marine Sciences Institute. “Our questions are about how evolution has produced this diversity and the places where they house that diversity—literally, physically—are museum collections.”

For the past three summers, Wainwright, his graduate students and a select number of undergraduates have journeyed to the National Museum of Natural History’s Museum Support Center, located just outside of Washington D.C., to collect data from preserved specimens in the National Fish Collection. In total, the team, working in conjunction with Assistant Professor Samantha Price of Clemson University, generated a dataset on 6,000 species and 16,000 individual specimens. The collection efforts were supported by a grant from the National Science Foundation.

Using the dataset, the researchers hope to answer elusive yet fundamental questions about fish morphology and the evolutionary history that led to such diverse body shapes.

“It’s about a fifth of all species of fish,” said Wainwright. “It’s by far the biggest dataset of its kind that’s ever been generated, but whenever you build a dataset like this, you enter the world where curation and management of the dataset becomes an unbelievably big job.”

An evolutionary biologists’ dream collection

Summer humidity in Washington D.C. can be brutal, but Angelly Tovar, a junior majoring in wildlife, fish and conservation biology, had a place where she could escape the heat. The Museum Support Center, located in Suitland, Md looks nondescript on the outside, but the building houses more than 31 million objects, including the largest collection of biological specimens preserved in fluid in the country. Its fish collection was started in the mid-1800s.

After passing through security, Tovar and colleagues would sift through a sea of fish jars, collecting multiple measurements from each specimen. They’d measure body length, fin length, jaw length and other specified data points. Working in assembly-line fashion—surrounded by racks of jars reeking of preservation fluids—each team member had a specific job, with Tovar acting as the group’s photographer, snapping fish photos for archival purposes.

“We had a group of three—sometimes four—measuring all the fish, putting down all the data at the same time,” she said. “We have very specific things that we look for.”

Victoria Susman, a senior majoring in wildlife, fish and conservation biology, said her 9-to-5 days consisted of collecting linear measurements from the fish using calipers. While the students were trained in measuring techniques prior to their summer assignments, there was a learning curve.

“I think I did like 20 [fish specimens] my first day and then by the end of it, I was pushing like 60, so you get really good at it over the summer,” Susman said. “Your fingers get very fast with the calipers. I definitely developed a caliper callous on my finger.”

Susman, who previously spent time working at San Diego’s Birch Aquarium and utilized the collections at the UC Davis Museum of Wildlife and Fish Biology, was awestruck by the enormity of the Museum Support Center. “The museum staff was extremely kind to us and kind of let us look at whatever we wanted to, so we had a lot of freedom to just explore and take some time,” she said. “You see some massive jars and some tiny jars with like hundreds of fish in them, so incredibly preserved.”

It was a magical moment for both Susman and Tovar, seeing certain fish up close and personal that so far they’d only seen in documentaries or learned about in class. There were sunfish, opah, kingfish and marlin. Sometimes, the students would play games, like who could find the oldest specimen. Susman recalled marveling at specimens collected by President Theodore Roosevelt.

“You’re measuring a fish that someone caught in the 1800s and that’s just such a powerful moment,” she said. “You’re really connected to a part of history that someone had the foresight to preserve for you to use later on in your research, and I thought that was amazing.”

Back to campus: a time for data analysis

With the dataset, Wainwright and his colleagues hope to solve mysteries surrounding the plethora of fish body shapes and produce

landmark studies in the process. As Wainwright sees it, fish—based solely on body shape patterns—can be divided into two groups: those that spend their time swimming in midwater and those living in contact with the bottom.

“Midwater fish are much more constrained and they’re much more limited in their body shape variation than fish that live in contact with the substrate,” he said. “So something about touching the bottom and interacting with the bottom opens up all kinds of other possibilities.”

“Many of the freakiest fish forms that exist are in the abyssal depths,” he added. “The rate of what we call ‘morphological evolution’ just goes really high when you get down to this sort of deep water.”

As Wainwright finalizes the group’s studies, his undergraduate students are exploring their own ideas regarding fish shapes. Tovar, currently a student researcher in Wainwright’s lab, is looking at the morphology of fish jaws, honing in on a novelty called the intramandibular joint, which allows some fish exceptional control of their lower jaw during feeding.

Meanwhile, Susman studied components of body elongation within different ecological groupings of fish.

“As you get down into the water column, when you have more substrate and more complexity in the habitat, you definitely find more variation and elongation,” said Susman, who presented her preliminary findings at last year’s Undergraduate Research Conference. Much of the data analysis in these studies requires the students know computer programming, like the R programming language. Susman wasn’t familiar with computer programming until she got involved in the fish collections project.

While some data analysis work still needs to be done, Wainwright is excited about the future.

“We plan on setting the world on fire with the papers we’re going to write with this,” he added. “And we’re going to be using a dataset largely collected by people who don’t yet have an undergraduate degree and we thought that concept was especially cool.”