Ian Haydon, ’12 B.S. in Biochemistry and Molecular Biology, Science Communications Manager at the Institute for Protein Design

Quick Summary

- Ian Haydon was a graduate student studying biological physics, structure and design at the University of Washington

- He discovered science writing after attending a talk on better ways to communicate research

- His writing has appeared in Scientific American and The Philadelphia Inquirer, among other publications

Ian Haydon’s entrance into science writing occurred in whirlwind fashion. As a graduate student studying biological physics, structure and design at the University of Washington, he was intent on obtaining a Ph.D. but also knew he was more interested in careers outside of academic research.

“One of my pet projects as a graduate student in the first couple of years was to try as many of what are sometimes called ‘alternative career options’ as possible,” said Haydon, who graduated from UC Davis in 2012 with a B.S. in Biochemistry and Molecular Biology.

Haydon had interests in public speaking and science communication but hadn’t tried his hand much at either. One day, he attended a campus workshop on writing for general audiences.

“The idea of the workshop was how to explain how to communicate your science to a broader audience,” Haydon said. “The woman running the workshop was an editor who was looking for people to pitch story ideas to be published in her online publication.”

The biology of chemical weapons

Haydon had a story idea. The April 2017 chemical weapons attack in Syria that killed more than 80 people had just occurred. At the time, Haydon’s research at the university’s Institute for Protein Design concerned developing antidotes for weaponized nerve agents. He pitched the story, went home and wrote an essay about the scientists such as himself working to “sap chemical weapons of their horrifying power” over the weekend. The essay was published the following week in The Conversation and was later picked up by Scientific American.

“It was really rapid,” Haydon said. “I went from just going to this workshop to try my hand and see if I can learn something to pitching and publishing a story.”

It was his first piece of science journalism — and the first time he actually enjoyed writing something.

“That article was the first thing I’ve ever written in my life that I wanted to write — that I elected to write,” he said. “And that made all the difference for me.”

Resident nerd of the newsroom

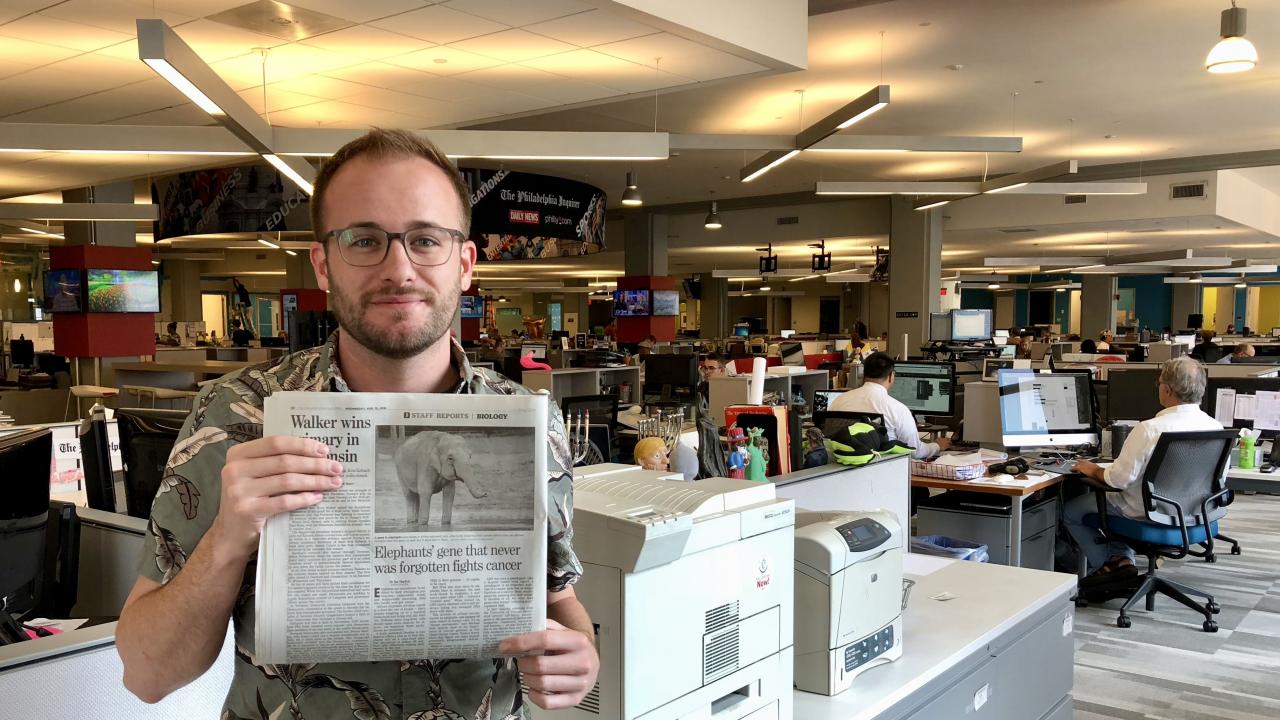

With a newfound interest, Haydon embarked on a new career trajectory. For about one year, he was a grad student by day and writing science stories by night. He built up a portfolio and eventually applied for the 2018 AAAS Mass Media Science & Engineering Fellowship, a program that places scientists in newsrooms with the goal of increasing public understanding of science and technology. Haydon was accepted as a fellow and landed in The Philadelphia Inquirer’s newsroom.

“It was a little intimidating,” he said of the experience. “It was a very different pace of work than I was used to, especially in the sciences where research often moves slow. Things don’t move slow at a daily newspaper.”

Editors and veteran reporters showed Haydon the ropes and for a summer, he was the newspaper’s “resident nerd.” The more technical the story, the more likely the editors would throw the story Haydon’s way. The assignments allowed him to increase his scope of coverage. As a freelancer, he had mainly covered biotechnology, but now, he was writing about particle physics, black holes, the opioid crisis and more.

“It was fun to interview scientists in other fields and try to translate their stories into accessible language,” he said.

With his career goals shifting, Haydon decided to rethink the Ph.D. track he was on. As a science writer, he found his technical science training useful but thought he didn’t necessarily need a Ph.D. to advance in the science communication field. He left the program, graduating with an M.S. in Biochemistry, and recently started working as a science communications manager for the Institute for Protein Design.

“Here, I’ll be writing about the science that’s coming out of the institute, of which there’s quite a bit,” he said. “It’ll be interesting to adjust to this new role and figure out how best to cover the exciting stuff that’s happening here.”

None of this would be possible without Haydon’s strong foundational knowledge of science, which was fostered at UC Davis.

Diving in to molecular design

Haydon enrolled at UC Davis as a transfer student following some time spent as a student at Sierra College in Rocklin, Calif. Through his combined interests in chemistry and neuroscience, he was turned on to the fields of biochemistry and molecular biology.

“I had an interest in neuroscience and was thinking that eventually, if I study enough chemistry, and study some biology, I might work my way into the brain,” he said. “I never really got there because I discovered that there is just so much interesting material, so much we don’t know, and so much left to be discovered, in that space between atoms and things like brains.”

At UC Davis, Haydon worked in the labs of Professors Ian Korf and David Wilson, and Lecturer and Project Scientist Alan Rose, all of the Department of Molecular and Cellular Biology. He went down the structural biology path and found that protein molecules piqued his interest.

“Essentially every protein has a unique structure and its structure gives rise to its function,” said Haydon. “For example, antibodies are proteins in the immune system and their structure is responsible for their ability to block viruses.”

That interest in proteins eventually led Haydon to become a junior specialist at UC Davis following graduation. He later worked as a research scientist on biofuels at the biotechnology company Novozymes. His graduate work at the University of Washington followed that experience.

“It definitely made sense for me to enter my graduate program and I don’t regret any of the moves that I made,” said Haydon. “But it’s never too early to start thinking about your next career move when you’re a student and to make sure you know about all the options available to you.”

“Any career change…comes with a little dose of fear,” he added.

For now, he’s focusing on his new role at the Institute for Protein Design.

“I see so many interesting things happening in the sciences but they’re often veiled behind jargon,” he said. “You won’t read about them on the front page of a newspaper unless they’re identified and translated into more approachable language.”