Social Media, Open Access and Confronting Bad Science: Q&A with Jonathan Eisen

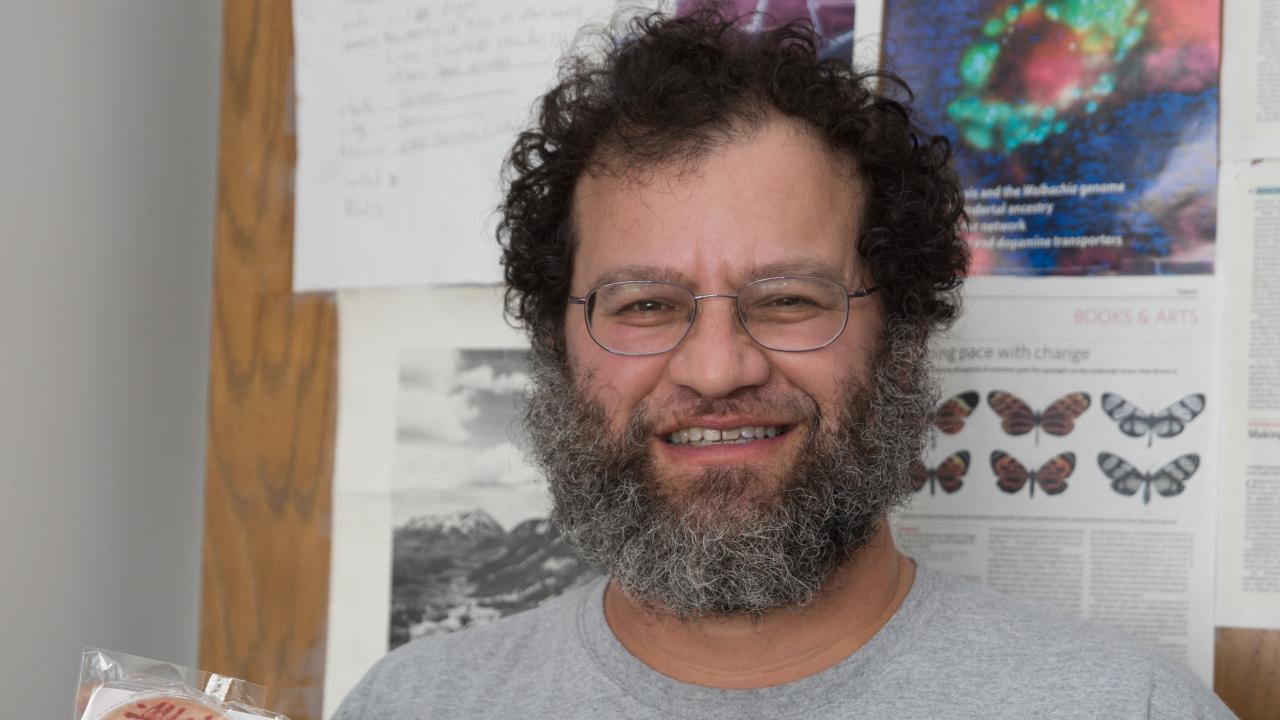

It was a bright, sunny afternoon at UC Davis when I sat down for an interview with Jonathon Eisen, professor of evolution and ecology. Eisen, who embraced social media as an early adopter, has amassed more than 41,000 followers on Twitter. He has positioned himself as a national expert on microbiomes and is an outspoken critic of pseudoscience. Over a bowl of chili and diet Pepsi, we discussed his use of social media, open access for education and the impact social networks are creating in the scientific world.

Lily Coates: How has social media helped you connect to fellow academics and peers, maybe in a way that you hadn't had before?

Jonathan Eisen: Well, the simplest way is it allows you to connect to people you've never met. I started using social media maybe 10 years ago. I was at a conference where people were talking about this and it really appealed to me. I think that that's one of the greatest things about combining social media and academics, you can connect with so many people and build a community without having to go to conferences or travel to other institutions. I started a blog, now called The Tree of Life, and one of the things that appealed to me most was that people could find out what I was doing without me having to travel.

So, you got this idea from being at a conference—did it give you the idea to jump on the social media craze?

No, I've always been into sharing scientific information, even when I was in school. As a graduate student, I started to do a bunch of work where I was posting data to these databases and I started to create my own sites to share some of the data from my projects. So, I've sort of always experimented with different ways to share data, samples, and figures.

When I first moved to Davis, I was invited to this conference at Google called Science Food Camp and I had no idea what I was getting into. I hadn't read any of the background information about the meeting, but it was at Google and I was like, "That sounds cool." And I got there and it was made up of maybe 100 people: founders of major tech companies, and Martha Stewart, and a group of people who said their job was science communication and science blogging.

I spent a lot of time at this meeting going to sessions on science communication and hanging out with these people and that was my first introduction to how one could use social media as a tool for science communication.I liked the idea that if I saw something in science that was interesting I could have a place to share it and I could point people to it. And that's how I used social media in the beginning.

So is this what lead to your interest in promoting open access to educational resources?

It’s related. I was already a supporter of open science before, but I was not as vocal in the public venue of promoting it. So, what I started doing was things like, if I saw something interesting that was in a less known, but open, journal, I would promote it. This is a reward to people for being open and I viewed this as a tool to help catalyze change without punishing people.

And that’s what I use Twitter for—and what I use a lot of social media for—just helping people share knowledge so that there is no longer a big advantage to publishing in closed places. Now people can find out about things regardless of where they're published and judge them by the quality of the work and not by the name of the journal where they're published.

Did you think, in a way, that you'd have to change the idea of science communications then? Because for so long, it's been based on who can get the most publications in Nature or Science, etc.

Yeah, and I'm not alone in that. I think that in what I call the "old model" of science—but of course it's still a lot of the current model—that all people want is to publish in one of these prestigious journals. And they spend years working on stuff just to get in there, and I personally think there's a higher probability of fraud in these journals because the pressure is just oppressive. And some people succumb to that pressure in order to get something into one of these places.

I think we need to change and digital publishing means that we can change. I think we can change the old model and just because there is a model does not mean it's optimal. That's what I actually care more about. Rather than saying that the old model is totally wrong, I think we need to experiment with other models and I think it's pretty clear from the experimentation done with open access publishing that the old model doesn’t work and it should be crushed and broken and destroyed. I'm still open to different parts of the old model being worth sustaining, but it has never been tested. It was just the way things were done, it was never tested.

What is the biggest benefit you've found from social media?

Well, I think without a doubt the biggest benefit to me is finding out what's going on in the world. I think I am more informed about the fields I’m in now than I ever have been and that is explicitly and solely due to social media. I think it's transformed my research to be much more cutting edge than it used to be; we find out about problems with methods, about new things to do, and about collaborators much faster and more efficiently.

I’ve gotten two or three grants directly from my social media activities and I've gotten many of the people in my lab from first interacting with them on social media. So it's transformed my work and helped me sort through news stories much more efficiently.

If I have a thousand people helping and they share just one or two (publications) that they think are interesting, on average, you cover almost all the papers. So you could write computer programs that would search through the literature that would find things you might be interested, but they're pretty mediocre compared to what people do. People can evaluate the literature, and the presentations, and the methods, and the YouTube videos.

You’ve achieved Twitter notoriety in part for your critiques of bad science, especially related to consumer products. Is this method of finding papers also how you got to find the 'snake oil" papers and other bad science stories like that?

I'm not sure actually. So, before I got into social media, before I moved to Davis, I worked at this big genome research center in Maryland. And I went there when it was still early in the field of genomics, before the human genome was sequenced, even though it hasn't actually been finished. And that statement right there, "before the human genome was sequenced, but it hasn't been finished" ate at me. I started to get really sensitive to the hype in genomics. People were talking about how when we finish the human genome, we will cure all cancers.

They were saying this in Congress! That's the justification people gave to spending two billion dollars of taxpayer money on sequencing the human genome. Now there have been many stories over the last few years about how the Human Genome Project did not lead to cures of all sorts of diseases and people in Congress have used this explicitly to withhold money from government science projects.

So, I already have this background in being really annoyed with the hype in genomics, then I move into this microbiome area and it's hot in 2006 or 2007. It's just getting popular and I see the same thing happening again, in a field I'm even more involved in. The Human Genome Project is incredibly important and I think revolutionizes medicine, but let's not lie about it.

And so same with probiotics. Like probiotics, some of them are incredibly useful and have been clinically shown to have benefits. But most of them have no data behind them and they're not regulated. They're treated like herbal medicine so you can claim anything you want.

In terms of snake oil, you can just walk down the street and you see it. In (convenience stores) there are these sections for probiotics for kids, boys and girls--there's no data on differences. There's a section for probiotics for adults, for probiotics for diabetics, probiotics for the elderly. There's no data on any of these things, and yet there's a huge hype over the benefit of probiotics.

What advice do you have for people who are interested in the consumer science aspect of microbiomes, and how can they make informed decisions when approaching microbiome-related products?

I think that the key thing here is there are two issues really. There's understanding the difference between correlation and causation which is a big problem in all of our society. So there's lots of data about differences in the microbiome between two groups of individuals. For example, kids with autism have a different microbiome in their gut than kids who don't have autism, on average. That does not mean that the microbiome caused autism.

In fact, kids with autism have different diets and they have a sensitivity to all sorts of different environmental cues. And, actually, the simplest model is that this leads to their microbiome being different. So I think that's the first thing for people to realize, that in any type of science—especially when it involves big data—correlation and causation are not the same thing and showing causation is actually really hard.

The second part of this is to just come to a balance between being terrified of microbes and the idea that all microbes are good for you. There's way too much sterilization of the planet and now there's this "all microbes are good for you and they're going to cure you of all diseases idea". Most microbes don't care about us, they care about food and reproducing and occasionally we're in the way and we can sometimes help them or hurt them.

Getting these two issues together are really important for helping people to think about microbes in the world and that's why I spend a lot of time trying to do outreach about microbes because I think people are smart enough to deal with this. People deal with this all the time in their daily lives. They can figure out cause and effect, they just haven't thought about that when they see an ad for fecal transplants curing their kid's autism.