Mark Huising Discovers "Beautiful System" in Insulin Regulation that Gives Clues to Diabetes

Sometimes, listening in on a conversation can tell you a lot. For Mark Huising, an assistant professor in the Department of Neurobiology, Physiology and Behavior at the UC Davis College of Biological Sciences, that crosstalk is between the cells that control your body’s response to sugar, and understanding the conversation can help us understand, and perhaps ultimately treat, diabetes.

Huising’s lab has now identified a key part of the conversation going on between cells in the pancreas. A hormone called urocortin 3, they found, is released at the same time as insulin and acts to damp down insulin production. A paper describing the work appears online on June 15 in the journal Nature Medicine.

“It’s a beautiful system,” Huising said. “It turns out that there is a lot of crosstalk going on in the islets to balance insulin and glucagon secretion. The negative feedback that urocortin 3 provides is necessary to tightly control blood sugar levels at all times.”

Diabetes affects millions of Americans every year. Both forms of the disease — type 1, “juvenile” or “insulin-dependent” diabetes, and type 2 or “adult-onset” diabetes — occur when the body fails to regulate the level of sugar properly.

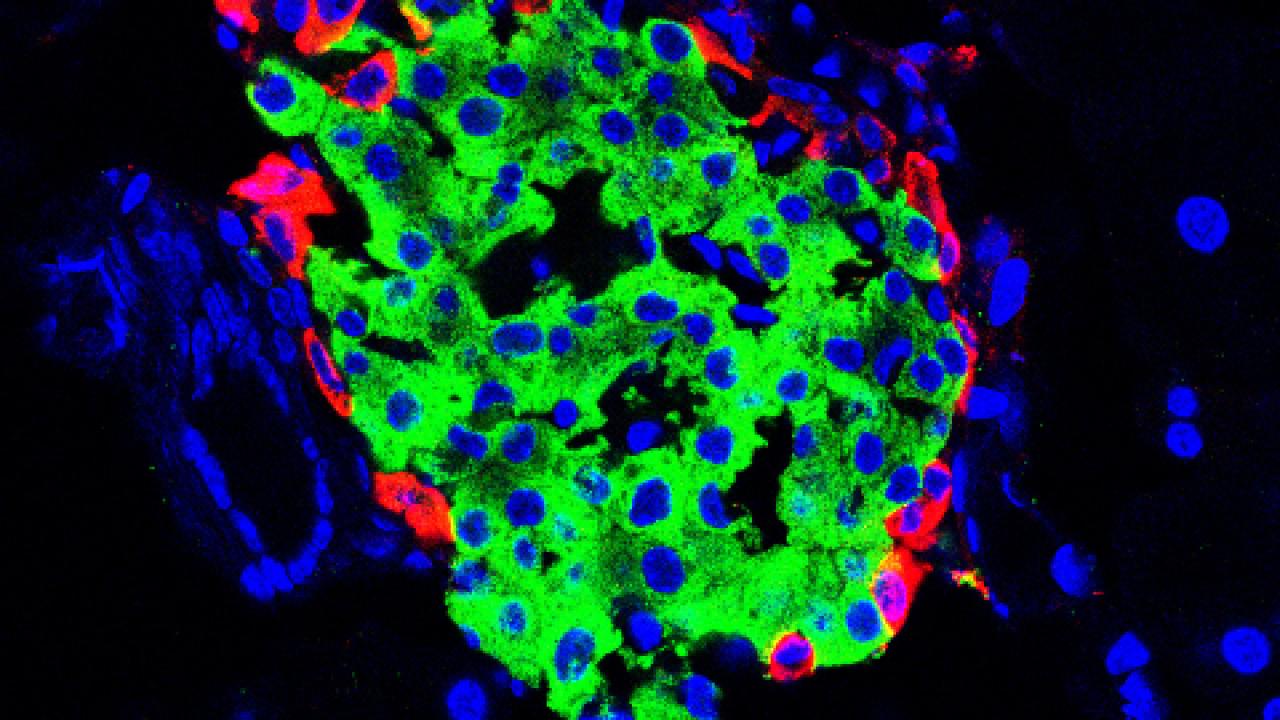

Diabetes is tied to structures called the Islets of Langerhans in the pancreas. Within the islets, beta cells make insulin. Increasing blood sugar stimulates insulin production, which causes the body’s cells to pull sugar out of circulation.

The islets also house alpha cells, which make another hormone, glucagon, which acts on the liver to release more glucose into the bloodstream.

Urocortin 3 was originally identified as a hormone that is related to the signal in our brain that kick-starts our stress response. Instead, urocortin 3 is produced by islet beta cells and stored and released alongside insulin. In a series of experiments, Huising’s group showed that urocortin 3 causes another cell type in the islets, delta cells, to release somatostatin, which turns down insulin production and acts as a natural brake on the release of insulin.

Urocortin 3 is reduced in laboratory animal models of diabetes and in beta cells from diabetic patients. Without urocortin 3, islets produce more insulin, but at the same time lose control over how much insulin they release.

By understanding how different cells and systems communicate to regulate blood sugar, Huising hopes to get a better understanding of what happens when this regulation goes wrong, leading to the different forms diabetes. Eventually this approach could lead to new ways to treat or prevent the disease.

Coauthors on the study were, at UC Davis: Talitha van der Meulen, Anna Hunter and Christopher Cowing−Zitron; Cynthia Donaldson, Elena Cáceres, Michael Adams and Andreas Zembrzycki at the Salk Institute, La Jolla; and Lynley Pound and Kevin Grove at Oregon Health Sciences University. The work was funded by the Juvenile Diabetes Research Foundation, the Clayton Medical Research Foundation Inc., and the National Institutes of Health.

Media Resources

- Read the paper in Nature Medicine

- Hartwell Foundation awards grant for work on juvenile diabetes

- This story first appeared on the UC Davis Egghead blog