Postdoctoral Researcher Explores Regeneration in the "Reemerging" Hydra

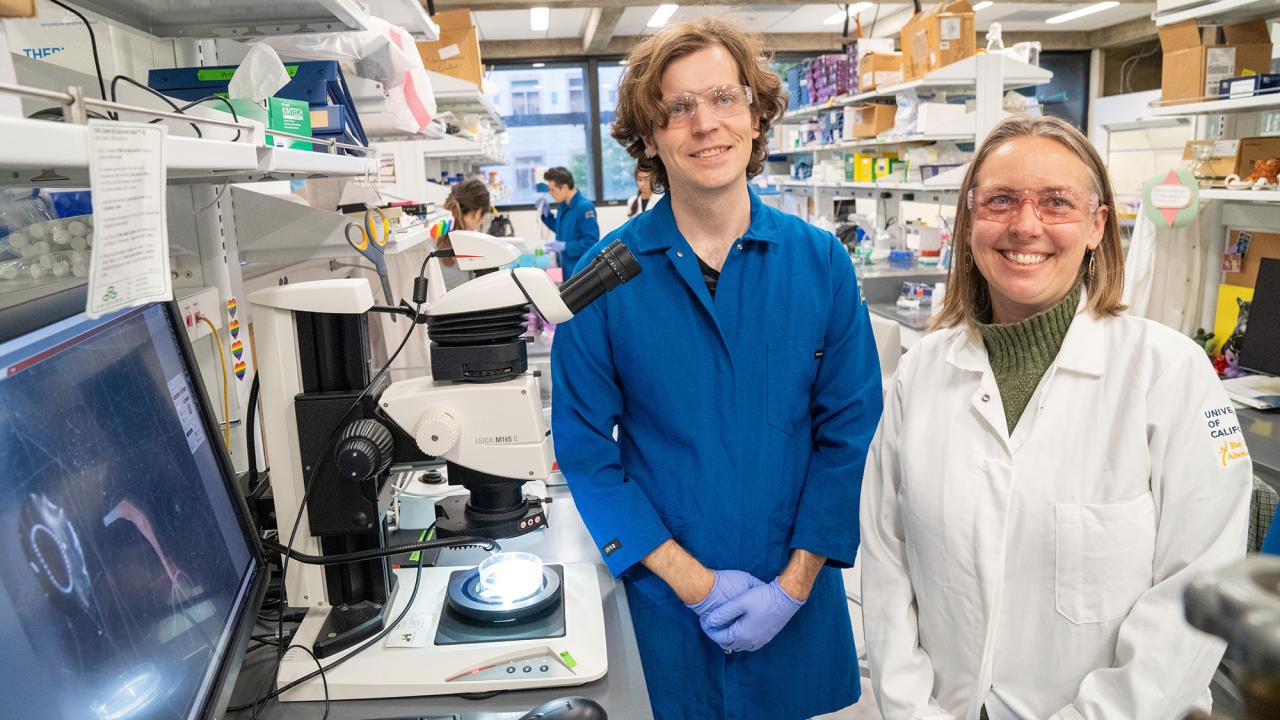

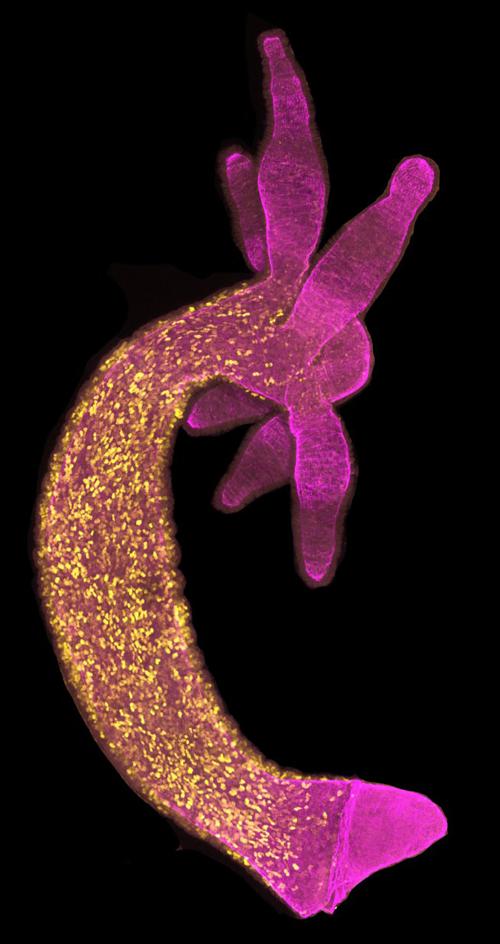

Ben Cox, a postdoctoral researcher in the lab of Celina Juliano, Department of Molecular and Cellular Biology, studies regeneration in Hydra vulgaris, a small cnidarian organism distantly related to the jellyfish. Cox is especially interested in tissue regeneration after injury and aims to determine how progenitor cells migrate and invade into injured tissues to restore lost cell populations, as well as how the extracellular matrix components are remodeled during this regeneration process.

Cox is a recipient of the Society for Developmental Biology’s (SDB) Emerging Research Organism Grant, and spoke with the society about his developmental biology journey, his scientific outreach efforts, and why he considers Hydra vulgaris to be a “reemerging organism.”

A lifelong passion for animals

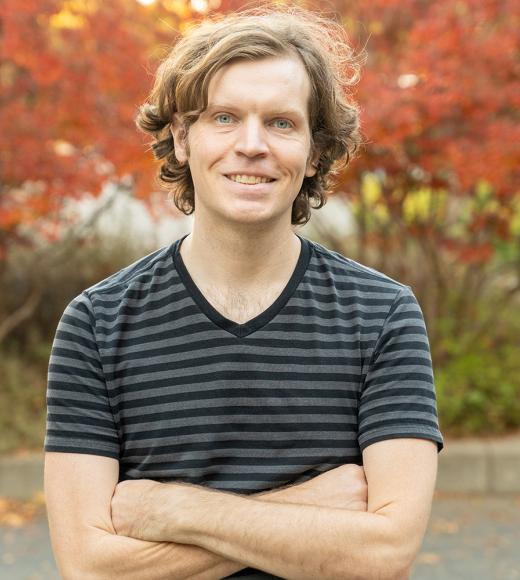

Majoring in biology at the University of Texas at Austin, Cox considered attending veterinary school as he has always loved working with animals. That he ended up in the world of developmental biology seems only fitting. Cox cites Sean B. Caroll’s Endless Forms Most Beautiful, as well as guidance from Professor Jennifer Moon at University of Texas at Austin as the catalysts for his first delve into research. Moon put Cox in touch with his future undergraduate advisor, Jeff Gross, with whom Cox studied zebrafish eye development and regeneration.

After college graduation, Cox worked as a lab technician for a year and a half in Kyle Miller’s lab at UT Austin. Cox studied the relationship between the human DNA damage response and cancer predisposition. He found this work compelling, but missed the beautiful imagery associated with development and regeneration and reentered the field through graduate school at Duke University. Cox joined Ken Poss’s lab as a Ph.D. student in the Genetics and Genomics program and studied cardiac regeneration in zebrafish. Here, Cox learned valuable lessons and techniques from Poss, including how important it is to develop your own toolkits for your organism.

Cox carried these techniques over to his current postdoc in the Juliano lab. Coming across the SDB Emerging Research Organism Grant call for applications, he questioned his advisor, “Does Hydra even qualify as an emerging model?”

Cox explained, “Hydra was studied for its regenerative capacities centuries ago, but fell out of favor as classic developmental genetic models such as fish, mice, flies, and worms solidified.” He states that Juliano and others in the field are bringing Hydra into the 21st century by taking advantage of new biotechnology such as CRISPR to develop transgenics, and siRNAs to modify gene expression.

The best of both worlds

The aspects of Hydra vulgaris that make it such a promising emerging organism also present some of the greatest challenges of working with it. Because Hydra does not have an expansive database of previous work to reference, researchers need to develop their own tools, assays, and transgenic lines for their studies. Cox refers to this as “the gift and curse of being in the emerging research organism field.”

A dedicated SDB member, Cox is no stranger to the mission of science education and outreach. During his time at Duke, he co-hosted The Endless Frontier radio show, which highlighted lesser-known research and scientific findings in the news cycle. Cox interviewed scientists from various fields and facilitated conversational science discussions, aspiring to make complex science interesting and accessible for non-scientists. Radio was a particularly great medium for Cox as he is a music enthusiast, citing his expansive record collection as the “pride and bane of his existence.”

Cox’s favorite part of joining the SDB community is the annual SDB conference, at which he presented in the Hilde Mangold Postdoctoral Symposium this year in Chicago. He is drawn to the breadth of research subjects and organisms discussed at the conference each year. When asked about his favorite part of being a developmental biologist, Cox cites the diversity of research in the field.

“We have the best of both worlds in the sense that our research asks and can hopefully answer fundamental questions about how organisms form that can have some biomedical relevance. But we also get to be over in the ecology and evolutionary biology playground of studying as many cool and weird animals as we want.”

For those looking to break into the developmental biology field, Cox says: “Be open to different research opportunities and research questions. If you have that passion for the questions, it’s transferable to different research projects.” He added, “Not limiting yourself to only working on one organism or one question is an important way to make sure you’re experiencing the breadth of what scientific research has to offer.

Media Resources

- Samantha Stettnisch is a communications intern at the Society for Developmental Biology.

- This article originally appeared on the Society for Developmental Biology's website.