Supporting Non-Linear Science Careers Strengthens Academia

Funding agencies and universities should make it more equitable for early-career investigators with non-traditional career paths to compete for grants and progress in their careers, argue four scholars with non-traditional backgrounds in a paper published in PLOS Biology in the fall of 2023.

Such changes would benefit women, underrepresented minorities and people of economically disadvantaged backgrounds – and bring a wider range of experience and expertise into academia, the authors argue.

María Maldonado, CAMPOS scholar and assistant professor in the UC Davis Department of Plant Biology and coauthors Anna Vlasits, Northwestern University; Monique Smith, UC San Diego and Simone Brixius-Anderko, University of Pittsburgh, themselves represent a tangle of career paths.

“We are … a high school dropout who re-started her education after having children; an immigrant scientist who left academia to work as a consultant and financial analyst for an extended period and then returned; a mother who started her family during her Ph.D. and left academia when the career became incompatible with parenthood, only to return later; and a first generation college student from a low socio-economic background who worked full time throughout her education.”

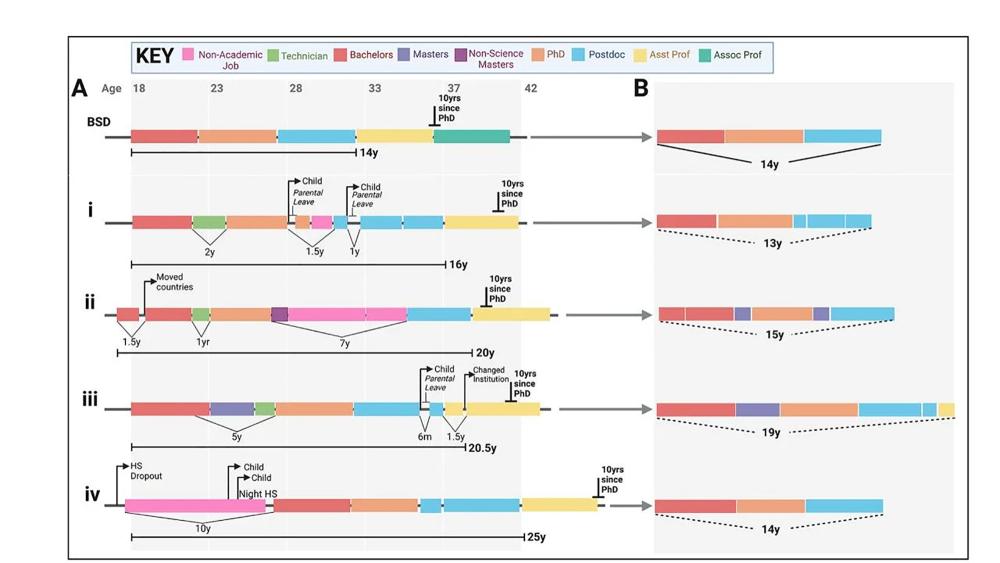

That contrasts with the traditional, linear path of the ‘Big Shining Doctor:’ bachelor’s degree, doctorate, postdoctoral research and tenure-track appointment.

Unfortunately, while non-linear career paths are increasingly common – especially among people from groups underrepresented in academia – funders, and hiring and advancement panels, still base policies and decisions on the traditional model. For example, the National Institutes of Health restricts ‘early career’ funding, intended to help young researchers establish themselves, to ten years after someone has received their doctorate. Age limits are also common.

“Some of these criteria are ageist and many are counterproductive to funders’ stated goals of diversity, equity and inclusion,” the authors write. Parenthood and comparatively low pay for graduate students and postdocs can push people off a straightforward career path, especially if they come from a low socioeconomic background.

Benefits of a non-traditional path

Indeed, the qualities needed to succeed in a non-linear career path – such as motivation, persistence, resilience and adaptability – are also essential for success in academia.

“The scientific community should embrace such resilience. In addition, job skills from working in other sectors are valuable and round out a faculty member’s abilities to run a lab,” the authors write.

To level the playing field, the authors propose funding agencies drop age caps and consider how they impose time limits. For instance, starting the “early-career clock” from the time of tenure-track appointment would be more equitable than starting it from time of Ph.D. graduation. Funders and hiring committees should standardize how they assess career breaks and gaps in productivity and consider ways to assess the knowledge and skills people bring from work outside academia.

“A broader understanding and support of non-traditional paths into academia will diversify science,” Maldonado said.

Maldonado, Vlasits, Smith and Brixius-Anderko are fellows of Leading Edge, an initiative to improve the gender diversity of life sciences faculty in the United States by providing women and non-binary postdocs with a platform to present their work, an opportunity to connect with one another, as well as mentorship and career development training from world leaders in biomedical research.

Media Resources

- Supporting nonlinear careers to diversify science (PLOS Biology)