Mussel Bed Surveyed Before World War II Still Thriving

Old Manuscript Leads Researchers to Biodiverse Mussel Bed and 101-Year-Old Scientist

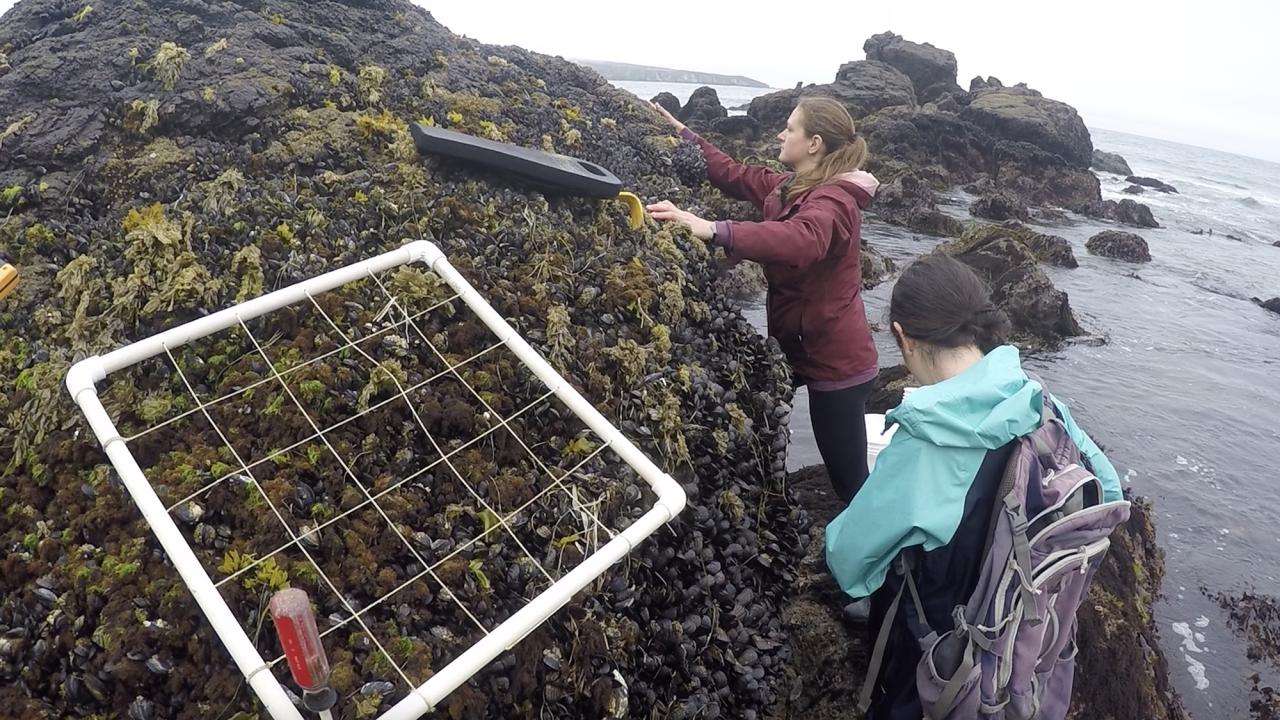

A mussel bed along Northern California’s Dillon Beach is as healthy and biodiverse as it was about 80 years ago, when two young students surveyed it shortly before Pearl Harbor was attacked and one was sent to fight in World War II.

Their unpublished, typewritten manuscript sat in the UC Davis Bodega Marine Laboratory’s library for years until UC Davis scientists found it and decided to resurvey the exact same mussel bed with the old paper’s meticulous photos and maps directing their way.

The new findings, published in the journal Scientific Reports, document a thriving mussel bed community that nonetheless shows the mark of climate change. Ninety species of invertebrates were found to live within the mussel bed — slightly more than those found in 1941. Among them were warm-adapted species more typically found in southern waters, such as the California horsemussel Modiolus carpenteri and the chiton Mopalia lionota.

“We anticipated finding dramatic losses of species,” said lead author Emily Longman, who conducted the study as a UC Davis graduate student and is currently a postdoctoral fellow at the University of Vermont. “We predicted we’d have a big decline in biodiversity. Shockingly, we didn’t find that. If anything, we found more species. This mussel bed community is really healthy.”

Living author

Adding to their excitement, the researchers learned after completing their survey that one of the old manuscript’s authors, Milton Hildebrand, was not only still alive at age 101, but living in nearby Davis as a retired UC Davis zoology professor. Longman and Sanford got to meet with the WWII veteran in 2019 before his death the following year.

“Transferring scientific knowledge across generations like this is more than just the numbers and data — it’s a very human endeavor,” said senior author Eric Sanford, a professor with Bodega Marine Laboratory in the UC Davis Department of Evolution and Ecology. “Watching Emily Longman, a graduate student, interact with this 101-year-old scientist who initiated this research project 80 years earlier, was wonderful.”

The paper’s other author, Harvey I. Fisher, died in 1994 after a distinguished career in zoology. Fisher and Hildebrand were UC Berkeley graduate students taking a field course when they conducted their survey, before Bodega Marine Laboratory existed.

“Milton thought the results we had were fascinating,” Longman said. “He was charming.”

Stretched mussels

Habitat-forming species, like mussels, kelp and coral, are foundational to marine ecosystems because they provide critical “housing” for other species. The authors of both papers counted and recorded every invertebrate species they found within the Dillon Beach mussel bed.

“I think of them as the Motel 6 for rocky shores,” Sanford said. “Crabs, snails, worms, limpets, sea cucumbers — all of these species find lodging down in these three-dimensional beds.”

Previous research documented a nearly 60% decline in species diversity among mussel beds in Southern California. Yet, little data was available to understand how Northern California mussel beds were faring. One mussel bed cannot represent the entire coast of Northern California, but the Dillon Beach study provides an encouraging outlook amid a sea of recent bad news for oceans.

“Anecdotally, having worked at Bodega Marine Laboratory for over 20 years, the types of mussel beds at Dillon Beach are what we see in Sonoma and Mendocino counties,” Sanford said. “In general, they appear to be quite healthy.”

The resampling effort showed no biodiversity loss compared with what Hildebrand and Fisher saw in 1941, but it did reveal a signal of climate change: The relative abundance of species had shifted.

Cool-adapted species with a northern distribution ranging from California to British Columbia and Alaska, had decreased. Meanwhile, warm-adapted species with a southern distribution ranging down to Baja California, Mexico were becoming more abundant. The authors said such a shift was expected given that ocean temperatures recorded in Bodega Bay have been increasing since the 1950s.

Mussel memories

Longman and Sanford said their study highlights the value of sources and data sets considered “nontraditional” by science — such as an old, unpublished paper by students completing a field course.

“Untraditional resources, like maps from long ago, Indigenous knowledge, and old photos, are treasure troves,” Longman said. “They’re the only window into the past for a lot of these places.”

The study was funded by the Bilinski Educational Foundation, the Rafe Sagarin Fund for Innovative Ecology, and the National Science Foundation. The researchers acknowledge Bodega Marine Laboratory’s librarian Molly Engelbrecht for her commitment to archiving and digitizing student papers so they can serve as historical resources for the future.

The authors also thank Hildebrand and Fisher, who wrote in their 1941 report: “We hope our paper may serve as a basis for an ecological study of the area by ourselves or others at a later date.”

Media Resources

- Emily Longman, University of Vermont/UC Davis, emily.longman@uvm.edu

- Eric Sanford, UC Davis Bodega Marine Laboratory, edsanford@ucdavis.edu

- Kat Kerlin, UC Davis News and Media Relations, 530-750-9195, kekerlin@ucdavis.edu

- Press kit of photos

- YouTube video: “The Importance of Mussel Memory” by Emily Longman, Bodega Marine Laboratory, UC Davis