Study Reveals How the Ovarian Reserve is Established

Fertility is finite for mammalian females. From birth, females possess a limited number of primordial follicles that are collectively called the ovarian reserve. Within each follicle is an oocyte that eventually becomes an egg. But with age, the viability of the ovarian reserve decreases.

“Despite its fundamental importance, our understanding how the ovarian reserve is established and maintained remains poor,” said UC Davis Professor Satoshi Namekawa, Department of Microbiology and Molecular Genetics.

In a new study published in Nature Communications, Namekawa and his colleagues, including project scientist Mengwen Hu and UC Davis Professors Richard Schultz and Neil Hunter, define the epigenetic machinery that governs the establishment and function of the mammalian ovarian reserve, providing molecular insights into female reproductive health and lifespan.

“In human females over the age of 35, you see a decline in fertility,” said Namekawa. “Our study may give us the foundation to understand how female fertility is established and maintained at the molecular level and why it declines with age.”

Pausing primordial production

When the ovarian reserve is established, all the oocytes in primordial follicles pause their development and can remain in such an arrested state for decades.

“Fertility is supported by these arrested oocytes,” said Namekawa, noting that some hitherto unknown molecular machinery pauses the meiosis process. “The main question is how can these cells be maintained for decades? It's a big question. They cannot divide, they cannot proliferate, they just stay quiescent in a woman’s ovaries for decades. How is this possible?"

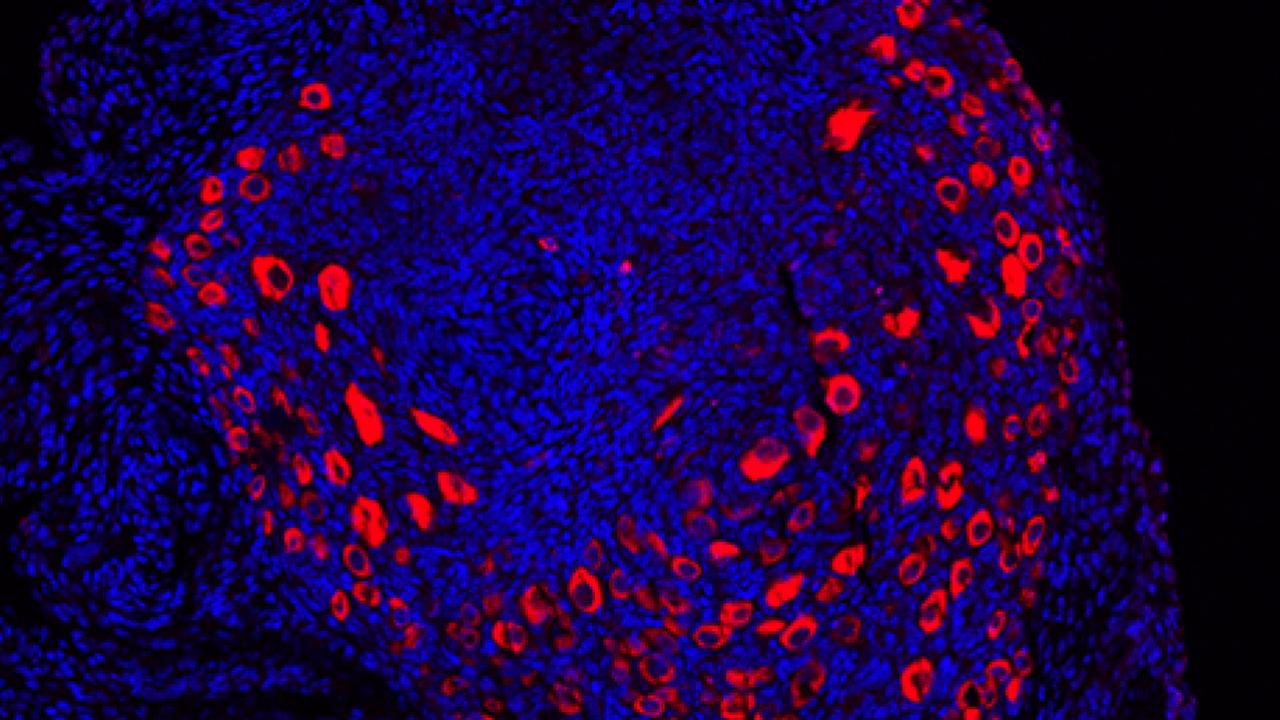

Using mouse mutants, the team highlighted the epigenetic programming that pauses the meiosis process at an early stage, leading to creation of the ovarian reserve. The researchers found that the pausing of this oocyte transition phase was mediated by a group of proteins called the Polycomb Repressive Complex 1 (PRC1).

A molecular understanding of fertility

PRC1 acts as silencing machinery, suppressing the meiotic process that occurs prior to establishing the ovarian reserve, thereby ensuring a proper gene expression program in the ovarian reserve. When the team created mouse mutants with depleted PRC1 machinery, they found that the ovarian reserve couldn’t be established, and the cells underwent cell death.

“We show that a conditional PRC1 deletion results in rapid depletion of follicles and sterility,” said Namekawa. “These results strongly implicate PRC1 in the critical process of maintaining the epigenome of primordial follicles throughout the protracted arrest that can last up to 50 years in human females.”

According to Namekawa and his colleagues, deficiencies in PRC1 functionality may help explain cases of premature ovarian failure and infertility in humans.

“Now that we found that this epigenetic process is key for establishment, the next question is can we uncover a more detailed mechanism of this process?” wondered Namekawa. “How can the ovarian reserve be maintained for decades?”

Namekawa and his colleagues will investigate this question next, attempting to further elucidate the mechanistic events that govern PCR1 machinery. By learning more about this process, they hope to remedy potential fertility issues that arise as females age.

Additional authors on the paper include Mengwen Hu, Yu-Han Yeh, Yasuhisa Munakata, Hironori Abe and Neil Hunter, UC Davis; Akihito Sakashita, Keio University School of Medicine; So Maezawa, Tokyo University of Science; Miguel Vidal, Spain’s Center for Biological Research; Haruhiko Koseki, RIKEN Center for Allergy and Immunology; and Richard Schultz, University of Pennsylvania.

The research was funded by the National Institutes of Health.

Media Resources

- PRC1-mediated epigenetic programming is required to generate the ovarian reserve (Nature Communications)