Discovering Curiosity: The Buggy Scent of Desire with Distinguished Professor Walter Leal

Quick Summary

- Walter Leal and his colleagues use reverse chemical ecology to identify sex pheromones in insects

- Identifying such pheromones could help mitigate agricultural devastation caused by insects

- While Leal’s research is used to ward off pesky insects, he notes that insects are vital to ecosystems

When discussing his chemical ecology research, Distinguished Professor Walter Leal likes to turn to a fatal tale of biology.

It’s night in the eastern United States and under the cover of darkness, moths emerge to copulate. A male bristly cutworm (Lacinipolia reinigera) flitters about, its antennae flicking and tasting the air for a female’s pheromones. It picks up a signal—strong and clear, and banks for it. But instead of a female moth, a chemical mimic lurks in the darkness.

“Like everything else, when we generate a communication there is going to be spying on that communication,” said Leal. “If a female produces a pheromone that attracts a male, there might be a predatory species that eavesdrops on the female’s signal or preys upon the male responder by luring them to their death.”

Our doomed suitor heads for his prize, sticky droplets attached to a swinging silk thread, and is snared. No female moth lives here. Instead, an American bolas spider (Mastophora hutchinsoni) draws the struggling male up into its fangs.

“They come for mating and they end up dying,” said Leal of the nighttime enterprise.

The American bolas spider is no one-trick pony when it comes to its enticing chemical mimicry. As midnight approaches, bristly cutworms retreat and smoky tetanolita moths (Tetanolita mynesalis) appear, the two mothe species active during different times of the night. The American bolas spider can chemically compensate for the moths’ different schedules, shifting the makeup of its deadly bouquet to match the pheromones produced by a female smoky tetanolita.

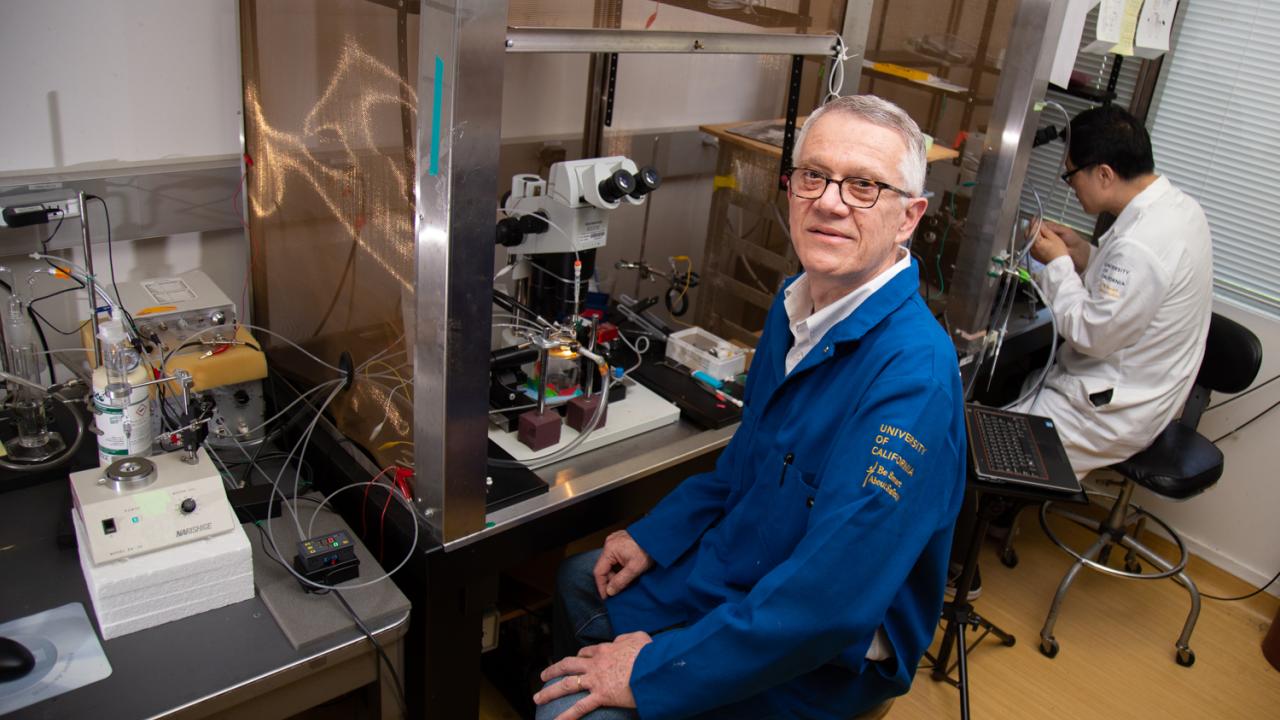

“Basically, we are bolas spiders,” said Leal of himself and the colleagues in his lab at the Department of Molecular and Cellular Biology at UC Davis, where they identify the enticing scents insects can’t stay away from.

Leal studies the molecular basis of insect olfaction, unraveling how insects detect chemicals and using that knowledge to inform pest management techniques. Most recently, he and colleagues identified a sex pheromone of the Asian citrus psyllid (Diaphorina ciri), a worldwide threat to the citrus industry that made its way to California in 2008. Identifying the pheromone could help mitigate the agricultural devastation caused by the insects.

Over the years, Leal and his colleagues have identified sex pheromones in many bugs, including moths, beetles, cockroaches, mites and more in an effort to understand the scent-laden world of insects.

Sniffing out research interests

Leal’s interest in insect olfaction started with a general interest in chemistry. Raised in the coastal city of Recife, Brazil, he became entranced with the subject thanks to his high school chemistry teacher Aloisio Sotero, who later held various government appointments including Minister of Education. While studying chemical engineering at Federal University of Pernambuco, Leal taught Sotero’s classes when the latter was called away on government business.

“In those days, they had a lack of instructors available, so the government would allow people even without a degree to teach in high school because there were not enough teachers,” said Leal. “I ended up going (to school) a bit longer than usual because I had so much teaching commitments that I could not take my entire set of classes.”

After finishing his undergraduate degree, Leal moved to Japan for graduate studies, picking up the Japanese language during a six-month crash course following his arrival. He eventually earned an M.S. in Agricultural Chemistry at Mie University in Tsu, Japan and a Ph.D. in Applied Biochemistry at University of Tsukuba in Tsukuba, Japan. When he learned of the potential negative impacts of pesticides, Leal switched from studying pesticide chemistry to studying insect chemical communication and olfaction. He continued research in a postdoc position at Japan’s National Institute of Sericultural and Entomological Science and was eventually elected Senior Research Scientist in Japan’s Ministry of Agriculture, becoming the first non-Japanese scientist to earn such a tenure position in the government.

In 1999, Leal attended an entomology conference in Las Vegas and heard about a job opening in the UC Davis Department of Entomology and Nematology. Leal previously applied to a mosquito biology position at UC Davis but didn't receive any nibbles on that application. He applied again and this time secured the position. He joined the UC Davis faculty in 2000. The transition was nearly seamless.

“I left Japan one day and I started here the same day because here, we are 16 hours behind,” said Leal. “I didn’t want a gap in my CV,” he joked.

‘Making scents’ of insect chemicals

For 13 years, Leal’s UC Davis home was the Department of Entomology and Nematology, College of Agricultural and Environmental Sciences, but in 2013, he was appointed to a faculty position with the College of Biological Sciences in the Department of Molecular and Cellular Biology.

“It was a better fit,” said Leal. “I still do entomology but my work is more biochemistry-oriented.”

Over the course of his career, Leal and his colleagues have published around 200 studies, making monumental contributions to the literature on insect olfaction and pest management strategies.

For decades, researchers didn’t know how mosquitoes detected the insect repellent DEET. Hypotheses abounded, but in 2008, Leal and his colleagues were first to identify the specific olfaction receptor DEET acts on. To do this, they employed a method called “reverse chemical ecology.”

“In normal chemical ecology, we would look at these species and find out what chemical communication they have,” said Leal. “In my approach, we are looking first at the receptors there are” and then figuring out what chemicals they’re used for.

Utilizing this method has allowed Leal and his colleague to identify similar receptors in other insects. Leal’s sex pheromone identification work on the Asian citrus psyllid could help Californians combat citrus greening disease by creating a management strategy that uses the sex pheromone. Such strategies are already in use. In southern California, farmers monitor infestations of the tomato pinworm (Keiferia lycopersicella) by laying out pheromone traps in tomato fields.

Insects, essential to healthy ecosystems

While Leal’s research is used to ward off pesky insects, he doesn’t want laypeople getting the wrong idea about

their crawling and buzzing companions. Despite the irritant nature of some species, insects are vital components of the ecosystem.

“People have to remember that there are creatures like the honeybee,” said Leal. “Without the honeybees, there would be no pollination; there would be no almonds; there would be no fruit.”

Even the blood-sucking, disease-carrying mosquito has its redeeming qualities, according to Leal. Its aquatic larva act as a food source for small fish.

“We hate that mosquitoes carry disease, but it is unintentional for them,” said Leal, whose research also deals heavily with repelling mosquitoes. “Everything has an importance in the ecosystem. We might be clever enough to manipulate them to some degree, not to cause some harm to the environment, but to avoid that they contact us.”

With mosquito activity ramping up, Leal recommended that Californians wear repellents when outside.

“I tell my students to wear these repellents,” said Leal. “They always think, ‘It’s fine, it’s fine, it’s fine.’ But if you get one of those mosquitoes with West Nile virus in here, that’s a serious problem.”